Advisory: this recipe is neither quick nor easy. However, potpies are so much a part of the New England vernacular that I felt I should include a recipe for one. In fact, immigrants who came to Plymouth on later boats often referred to the resident Yankees as “pie eaters.” It is believed that the Pilgrims made pies, both savory and sweet.

New Englanders make potpies using meat or seafood. Because I boiled a whole chicken this week to make chicken stock, I used the white meat to make curried chicken salad and the dark meat to make potpies. Leftover turkey may be substituted. You can simplify this recipe by using store-bought pie crust and a 10-ounce combined package of frozen peas and carrots. While a bit labor-intensive, this is the kind of food that satisfies on a cold, blustery day.

Pastry for double-crust pie (recipe below)

1 small package of frozen peas

1 medium onion, chopped

3 carrots, peeled and diced

¼ cup (a half-stick) butter

1/3 cup all-purpose flour

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon dried sage, marjoram or thyme, crushed

1/8 teaspoon pepper

2 cups chicken broth

¾ cup milk

3 cups cubed chicken (can also use turkey)

¼ cup snipped fresh parsley

In a large pot, cook onion and carrots in two tablespoons of butter until vegetables are tender. Add dried herb of choice, salt and pepper; sauté a minute or two. Add remaining butter. When butter is melted, add flour and cook two to three minutes. Add chicken broth and milk. Cook and stir until thickened and bubbly. Add frozen peas, meat and parsley. Cook until bubbly.

Pour mixture into four to six individual casseroles. Roll out pastry. Cut circles to fit casseroles. Place pastry over dishes, pressing gently over edges. Cut slits in top for steam to escape. Brush tops with egg wash, milk or cream, if desired. Bake in a 450-degree oven for 15 to 20 minutes, or until pastry is golden brown. Makes four to six servings.

Basic pastry

1-1/2 cups flour

½ cup butter, cubed (or combination of lard/shortening and butter)

½ teaspoon salt

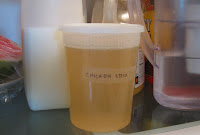

Ice water (about a half-cup)

Add salt to the flour. Work in butter with finger tips, pastry cutter or two knives until mixture resembles coarse, pea-size crumbs. Gradually moisten with ice water until dough holds together. Form into a disc, wrap in wax paper or plastic and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes.